Beyond being just ‘Smart’, the Senseable City is the city of the future: digital, connected, and more attentive to the needs of the people who live there. It’s early morning in Boston as we discuss the real goal of design, the shifting relationships between cities and nations, and the talent economy, while simultaneously trying to understand whether senseable cities will make us senseable humans or not. Carlo Ratti runs a lab at MIT where he creates interactive, digital environments in order to better understand cities, using this data to create tools that empower citizens and transform the urban environment.

What’s the difference between a smart city and a senseable city?

The principle is very similar, it’s just about emphasis. A smart city, to me, puts a bit too much emphasis on technology. A senseable city, which in English has a double meaning – to be able to sense as well as to be sensible – puts more focus on the human side of things.

A senseable city targets societal issues. How do you research the issues we will have to deal with in future?

Sometimes we just have an idea and then we work on it. Other times, it comes from the bottom-up within the team or from the outside, for example, from a company who solved a problem that inspires us. It’s more about how you find an inclusive solution that engages people.

And what methods do you use to find these problems in a bottom-up way?

We constantly discuss ideas. The important thing is to be able to tell a good idea from a bad idea. It’s what Hemingway used to call the bullshit detector. What is bullshit and what is not?

What does a city need today?

The needs today are the same as 10,000 years ago when cities first started. It’s about facilitating interaction between people.

Are there any issues being overlooked in terms of research?

Not really. I think there’s a lot of research going on all over the world.

The challenge is that you need to bring together many different disciplines. You need people who know the physical city, for example, designers and planners. People who know the technological side, such as engineers and computer scientists, but also mathematicians and physicists. And then you need people who deal with the social sciences, to look at the impact on people. You need to look at all these vectors and bring in people who speak different scientific languages.

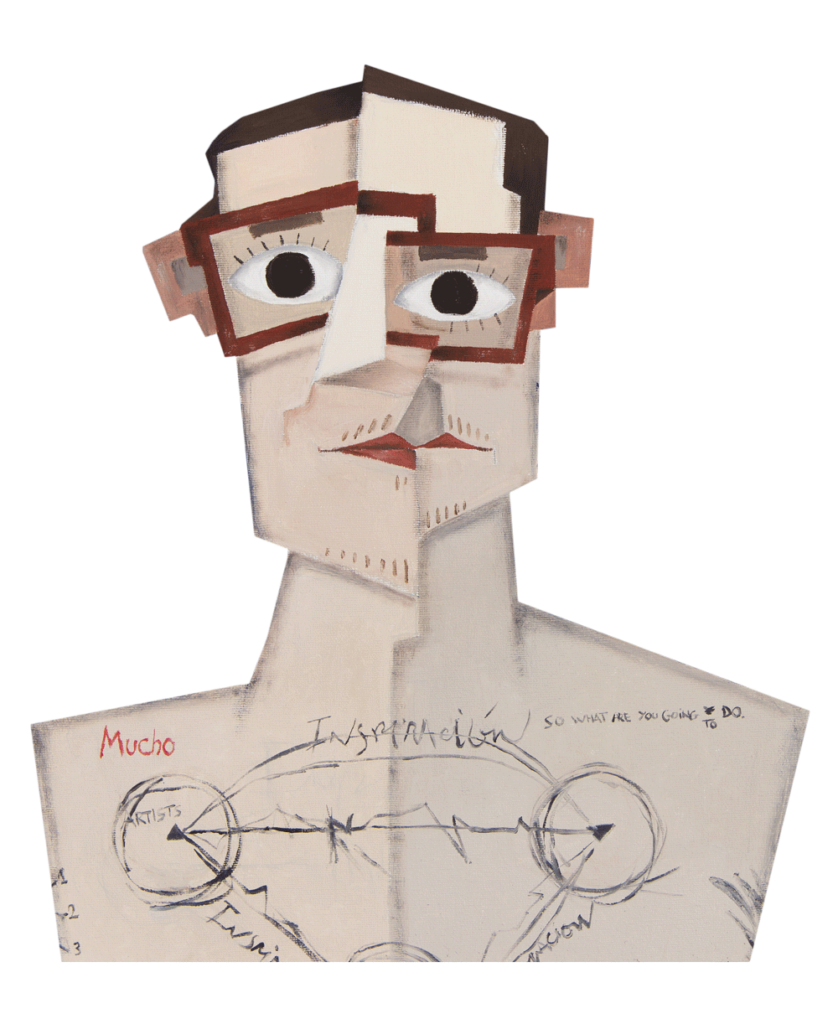

Do you involve artists in your boards, depending on the project?

The definition of artist is tricky but sometimes we collaborate with artists as well, yes.

What do you think is the role of design today? How has it changed over the last few decades and what is it today?

Tell me your definition of design, then I will tell you its role.

Solving problems?

Well, I think design is the opposite of solving problems. If you think about the most beautiful piece of design in the 20th century – the internet – we’re certainly not solving a problem; we’re following a dream.

I think design is about creating mutations in the artificial world that can lead to evolution. The internet was just following a dream to connect computers, but it ended up changing the way we buy, move, meet, mate, everything. It didn’t solve a problem.

Design is about exploring mutations in the world of the artificial. The most beautiful definition of design was given by Nobel Prize Winner Herbert Simon, one of the greatest researchers of the past century. He said, “The natural sciences look at how the world is. Design looks at how the world could be.” Design is dreaming about how the world could be.

Design needs to have a vision.

It’s about thinking about how things could be different. Injecting new artefacts into our cities, homes, and lives. Artefacts that can transform them. Design is about what is not there yet.

You don’t believe in predicting the future. So how do you sense things that are not there yet? Is it intuition, research or both?

First of all, you need to have some limits. You never know, and there can be a lot of unexpected consequences.

Natural evolution works by random mutation. But in the artificial world, it’s not just about random mutation. As a designer, the important thing is that sometimes you explore the mutations that go in the direction you want, but sometimes you explore those that go in the direction you don’t want. Why? To create antibodies. To encourage critical reflection. That’s critical design: a design that promotes a conversation and helps us to stay away from possible future traps.

Over the last few years, everything has changed in terms of politics. How is this affecting our concept of a city?

A city stands for the opposite of something closed. A city has always been a free space, an open space where people come together. In the Middle Ages in Germany there was a saying, “The air of cities makes us free.” The city has always been a place for freedom and experimentation.

What’s happening on the global stage is about closure, about protection, about walls. So the role of cities is becoming more and more important, because they preserve important values related to openness and inclusivity.

It’s not a surprise that, if you look at the past elections in the United States, almost all the big cities didn’t vote for Trump. Trump’s supporters were mostly in small cities or in rural areas. There’s a beautiful analysis by The Economist which plotted Democrats and Republicans against city sizes at the last election. The divide is clear. To me, cities are important because they are the places where resistance can be organised.

There’s a growing detachment between cities and nations. This is happening in United States as you mention, but it’s also visible in the vote for Brexit and in what’s happening between Catalonia and the Spanish state. It’s kind of visible everywhere. Do you think we are entering an age where the city has a different role? Can the city be more important than the nation?

Well, we’ve seen city-states take off in the past. I think what we’re seeing is nation-states trying to regain power. Populism is trying to bring back power to a national level. It’s almost like the last test for nation-states to survive.

There’s no doubt that cities are at the core of this battle. If you look at our planet from space, you see cities; you don’t see nation-states. Populism might be the last kind of attempt by nation-states to survive. But in the long run, certainly, cities have a better chance.

Nations and cities, openness and closure. Are you involved in any project that targets this issue in terms of raising awareness and fostering collaboration?

I would say that all our projects aim to raise awareness. For instance, we have done a lot of work on raising awareness around waste. Now we are doing quite a lot of work on segregation in cities. Again, the goal is very similar. I think all of our projects have a very strong stance. We look to raise awareness around a particular topic.

We’re based in Barcelona, a city that in the last year has been shaken up by many different events —from the terrorist attack to the Catalan referendum and the constant debate about mass tourism.

What’s the status of Barcelona as a city today?

I very much like Barcelona. I have many friends, I feel at home. I think Barcelona is facing, like many other places, a tension between cities and nation-states. There’s a lot of experimentation, a willingness to try out new things, acting as a lab to experiment with major issues. You mentioned them before. The issue of tourists, the issue of migrants, which – as they are transient population – is not that different to tourism. Issues of segregation, new technologies, job losses.

Regarding the topic of tourism, for example, many think Barcelona is facing the same problem as Venice. It’s attracting tourism in a way that’s not healthy, but at the same time it’s moving towards becoming a smart city. It’s investing a lot of funds and resources into innovation and digital growth. Could this be a solution?

Today you will see polarization. We have people who stay in the city for very little time; tourists. And we have people who stay for life; residents. The point is that when you get more and more tourists, you get a community that’s bringing money but also using the city. If you’re just a tourist, you don’t have any responsibility towards the city, and that’s what’s creating all of this tension. So I think what we need to do is somehow define a new citizenship.

We need to use technology to define an ‘intermediate’ citizenship with many different faces, where it’s not about whether you spend one day or your whole life. And that citizenship is something that will persuade people to stay longer, to be invested in the city, to contribute, and, of course, to have rights. Rights and responsibility come together.

This kind of special intermediate citizenship can be applicable to new models of living and housing. Increasingly both the last leg of millennials and Generation Z are finding, seeking and demanding more flexible, collaborative ways of living.

Co-living and co-working offer an infrastructure to define this new kind of intermediate or viable citizenship. Already today, some of the big institutions and companies across Europe, are allowing you to work wherever. For instance, we’ve been designing the Milan Talent Garden. If you sign up in Milan, you can easily just exchange your place in Milan with a place in Barcelona or Berlin. These models are becoming possible because new technologies allow you to be more flexible, as you say, and the same is true with co-living.

What are some example solutions you’re seeing in terms of co-housing and co-living?

I think there are two components to co-living and co-housing. The first is the type of apartment. We’re working on a project in Turin at the moment. It’s an old barracks, and we’re imagining a co-living situation where your apartment can be a bit smaller, but you share many services with other people inside your community. It’s very basic. Why do you need to have a 10-seat table in your apartment when you use it, maybe, just once every two weeks? If you share, maybe within a nice communal kitchen, it becomes a fun place. And it makes your house more affordable. So in principle, it’s co-working, but brought into the world of living.

Now, the second component is not only about trading space. Co-living is a way of mixing different communities. For instance, in China we’ve started working on a project that brings together the student community with the elderly community. Bringing together different groups that have complementary needs, and then building on that. So when it comes to co-living, one component is the sharing of space, but the other one is the sharing of different parts of society between different communities. For instance, the young and the old.

You mentioned the idea of talent. Most cities are seeking (or trying to retain) talent. What kind of talent are cities seeking, and how should they retain it?

That’s a good question. The discussion about talent has been framed by Richard Florida. He wrote a book about the growing importance of creativity and the emergence of a class of people unified by their engagement in creative work. With talent comes economic growth. But you can’t just focus on that. The problem is, as Richard himself mentions, you end up gentrifying the city, kicking out all the people who aren’t part of the creative class but who all together make large sums of money and therefore making the whole community much less rich. And so, the focus going forward should be on education, on training, because if you do that then you’re not just replacing one population with a more skilled population who makes more money and kicking out the people with a lower income, but actually allowing everybody to transform and grow. This idea of reskilling and upskilling is going to be crucial in tomorrow’s cities.

How can a senseable city help us improve as human beings? Can we learn from a senseable city and be more human?

That’s a good question. Technology is usually neither good nor bad. It really depends on us, on how we want to use it. For instance, if you look at what has happened over the past few years with the fact that we’re always connected now. People use technology to interact with people, but also to separate themselves. So I think it really depends on the value we put behind it. And I think that’s where experimental cities like Barcelona can be interesting places to see which way we want to use technology. It can lead us in two different ways and it’s up to us to decide which way we want to go.

This leads me to another question. You talk about a senseable city, a city that needs data to flourish. Many modern thinkers embrace the idea of implementing nanotechnology and biotechnology inside a human body in order to read our body function and wire us somehow to a bigger system. Yuval Noah Harari’s Homo Deus brought this question to the table. According to him, even humanity will turn from Homo Sapiens to Homo Deus. What are your thoughts on this? Are we going to be gods?

I was actually discussing this with Harari in India just a few months ago. He has a point for the following reason – we all know the problem with singularity, when artificial intelligence becomes more powerful than human intelligence. And when that happens we only have one option, an alliance between natural and technological evolution. A kind of convergence between the two, which can speed up the laws of natural evolution. This increased pace of development will be a necessity if we want to be part of the equation. It’s about a human/machine alliance. So I agree with that reading by Harari. It’s something we’ve been exploring as well.

Still, Harari’s thesis is also that somehow an algorithm will know more about our will and our desires than we do, because we judge things by experience. We trust our narrative self. We have these voices inside our heads, but it doesn’t actually match our will. Do you share this statement with him?

Things could get a little bit complicated because you need to separate the processing power a machine has from our knowledge of our body and of the world. I don’t think there’s a solution. We need to explore how we can achieve different kinds of integration between natural and artificial intelligence.