Andrew Losowsky used to think up interesting ways of telling stories. Then he decided it was time to let others speak. As head of The Coral Project, which wants to turn newspaper comments sections into actual community spaces, he found out how hard that is – not only due to disruptive commenters, but because most news organisations don’t know how to listen to their readers.

- The problem with online comments

- Why news organisations need to rethink the role of the audience

- Readers as the solution, not the problem

- Dealing with abuse

- The importance of design thinking in journalism

- Making silenced voices heard

- How to come up with ideas ...

- … and how to make them better

- Why one would stop telling stories

And what do news organisations want?

What we hear a lot is, “We want people to be nicer, we want people to have a genuine conversation.” And then we ask why. Why do you care about that as a news organisation? What is the role of the audience in your journalistic mission? What could it be? And most news organisations do not know how to answer that. That’s because for them the internet comments came in the box with the internet when they opened it. Most news sites used blogging platforms when they first created websites, and those had comments on them, so this seemed like a space that was there. And then people started talking and that seemed like a thing to have, so they left it there. Without proactively deciding what else this space could be. So by asking these bigger questions about the role of the audience in your journalism, what we’re trying to do is to push away from the common instinct – how do we make it less bad? – and to a much bigger question – how do we create something that is positive and connected to everything else we’re doing?

That sounds like a very noble and worthwhile goal. But how do you get from this big idea of reframing relationships to actual, useful tools?

One of the tactics that has been tried in the past is to force journalists to moderate and reply to comments on their pieces. It doesn’t tend to work. So instead of getting journalists to do community, we are using community to solve some of the problems that newsrooms have. We have done an enormous amount of user research. We’ve spoken to more than 300 people in more than 150 newsrooms in 30 countries. One thing journalists we interviewed have named as a problem is finding good sources. I’d ask, “What if you had a way to find those among your readers, who really are the experts?” And the response I would usually get was, “That would be amazing but we don’t have any way of doing that. That’s impossible.” That gave us a list of things we want to achieve with our tools.

So what do those tools look like?

Well, they are tools that allow you to ask specific questions to community members. To gather and hold that information, and search it, and sort it, and filter it. They are tools that allow community members to know what the newsroom thinks it knows about you. Tools that allow the journalist to sort, filter and search through existing contributions, whether in the comments or elsewhere, and then take actions on that. That action could be, send all these people an email. Send them a draft of my piece. Invite them all to an event.

Are you addressing harassment and trolls at all?

Yes, very much so. I think trolling is a complicated word because it can mean saying something sarcastic or funny, but it has also come to mean abuse. Let’s just call it what it is. It is abuse. It threatening and it is often illegal. So we are absolutely looking at ways of dealing with abuse, harassment, trolling and so on. For many people we’ve talked to who’ve been harassed, the big problem is not that people say this stuff, but that it appears in a way that makes it very hard for them to ignore: in their inbox or in their mentions. And if they want to find good comments they have no choice but to wade through the worst of the comments against them. So we’re looking at tools to help filter, sort and move away certain comments that people might not want to see. This is not an opaque algorithm. This is about allowing people and newsrooms to run their own algorithm, to create their own space where they feel safe, and add more diverse views.

In a post on the Coral website, you say that you’re working according to the principles of design thinking. What does that mean?

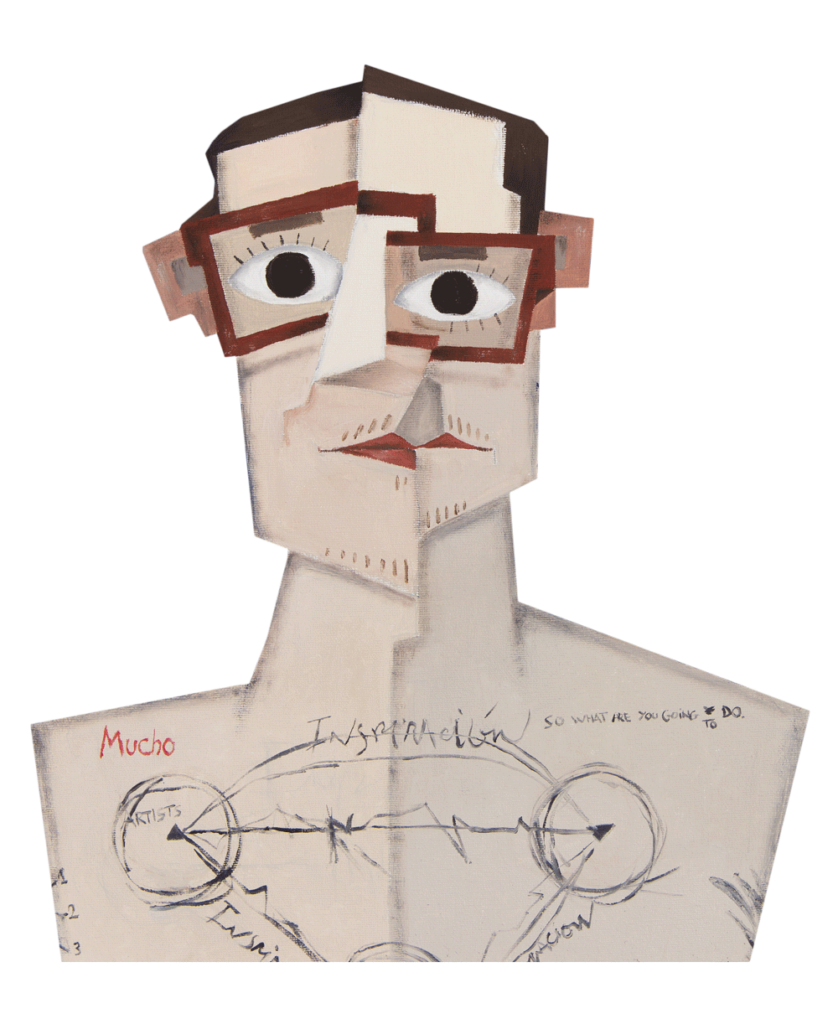

Design thinking is another term for user-centred design. It’s a methodology I learned at Stanford’s d.school. For me, there is a difference between design and art. Art is trying to express something for yourself to an audience. Design is trying to solve a problem for other people. Design thinking focuses on a lot of user research and rapid cycles of feedback. The process allows you to iterate and build prototypes very quickly, to test them and your assumptions, and then learn quickly from those assumptions and go all the way back and start again. Slowly you move towards building bigger pieces to test because you’ve learned more and more as you go along. What it means for us in this project is a lot of interviews, a lot of research, a lot of testing things out with people all the time.

Do you think that Design Thinking has other applications in journalism?

It’s certainly true that journalism traditionally has seen itself as very separate from the audience, broadcasting out information that we as journalists believe is important. There is a certain arrogance in that, I suppose. Sure, we get some feedback in terms of page views, but really understanding the context of those page views is very difficult. We’ve come to a point where we are staring so much at the things we can measure that we’ve lost track of the things that are harder to quantify. That really comes down to understanding what it is that people value.

Journalism is in a moment where it needs to justify its own existence for society and democracy. What is the role of journalism now? The only way that we can really understand that is by talking to people.I believe the future of sustainable journalism is working with the community, and the journalist’s role in that community is to be the fact checker, the investigator, the person who helps people understand and question how we got to here and where can we go next. The journalist does not have to have all the answers. You have experts in these communities. So I feel like design thinking in its purest form – understanding what is important in people’s lives, trying things out, learning, and testing our assumptions – is very important for the future of journalism.

You gave a TEDx Talk in 2014 in which you said that people who have a platform need to stop talking. Instead, you said, “We should give a voice to people we don’t hear from often enough.” Is that why you joined Coral?

It was certainly a very big motivation. But when I say people with a platform need to stop talking, I don’t mean they need to be silent. I mean they should use their platform, their audience and their communities to lift up voices of people who are either deliberately silenced or not usually heard from. One of the main things that attracted me to the Coral Project is that the comments now are overwhelmingly white and male, and these voices are drowning out other people. If there is a way that we can help journalism involve a greater diversity of voices, and for those voices to feel like the organisations take what they have to say seriously, then everybody gains.

Does that also mean for you, personally, to put your voice out less?

That has been what I’ve been doing in the last few years, yes. I have been writing a lot less. I am much less interested now in having a career that involves me being a figurehead. My role in the Coral Project is that of a manager, to support the work of my team. We’ve worked very hard to have a very diverse team. If we didn’t we would not be able to succeed in reflecting different voices in the tools that we build.

Your editorial concepts that strike me as unusually clever. You’ve written a book about doorbells. You’ve built a museum in a street. You’ve published a magazine around a volcano. You generally like to take people by surprise. How do you come up with ideas?

Neil Gaiman was once asked where he gets ideas for a story and he said that there’s a small man he just sends a blank piece of paper to and pays $20 and the idea comes back in an envelope. I don’t have a straightforward answer but I guess there is a common thread through my projects, which is that I become interested in a medium and its limits – when it breaks if you push it too far and the narrative just can’t sustain itself. However, now I’m thinking much more about the problems of people who are accessing this medium. Who am I aiming towards? What is the right medium to tackle a certain problem or reach an audience? I start with some limitation – whether that is audience, medium, or the narrative we want to tell – and then try to find the most appropriate, interesting, impactful, narratively satisfying way of doing that.

That’s great, but what I want from you is practical advice. We all get stuck. I might have an initial idea and then don’t know how to go on. What do you do then?

I often start a project by doing an envisioning process. I imagine that I’m one of the target audience members of this creation. And I don’t even know what this creation is yet! Then I imagine it like a dream. You know how in a dream the details are kind of vague? You walk up to the thing that you are making. Let’s say it’s going to be a book. So you walk up to a table, on that table is the book. Pick up the book. What is the first thing you feel? Write that down or record it somehow. Then open the pages. What are you feeling now? What are the thoughts going through your head? Then put the book down. What is the next thing that you do? Do you tell someone? Do you put the book in a prized place? Write down all of those things – what you feel, what you think, what you do – and keep those next to your desk. As you develop an idea, turn around and look at that list again and ask yourself, “Does this answer that?” If it doesn’t, something has to change.

Feel, think, do. Got it. Again, looking at all the things you’ve done, what struck me is that they never seem straightforward. They never seem to take the easy route. There’s always an extra twist to it. It seems to me that’s a challenge you create for yourself, but do you do it for yourself? Do you need it to be happy or do you do it for others?

I think that I get bored very easily. And I get bored by things that are predictable or obvious. When I start a project, I write down the first things that come into my head. Those are the things I won’t do. Because if they’re the first things that have occurred to me, they’re probably really obvious ideas, and if I don’t write them down, they stay in my head as possible ideas. This way, I’ve got rid of them. I don’t know whether that makes me happy, but it certainly stops me from getting too bored.

Andrew, most people active on the internet follow one rule: don’t read the comments. You must have read a lot of comments over the past few months. What has that done to you?

You’d have to ask the people around me, I suppose. I don’t think it’s changed me. But who knows? This is actually a more serious problem for those who have to read abusive comments on a regular basis. There is a certain trauma that moderators can suffer from being compelled to read so much unpleasantness. Which is not to say that all comments are unpleasant – in fact, far from it. I think that it’s the worst of them that tend to sit most with us rather than the best. That’s human nature, I guess.

We all think we know what’s the trouble with online comments: anonymity, the lack of regulating influences, and possibly that people are just fundamentally terrible. From your work, what have you learnt is the problem?

The idea that people won’t put their real name in front of terrible comments is just patently not true. On Facebook, people say the most vile and horrific stuff under their real names, often with a profile photo of them holding their baby. Anonymity is not itself a problem. The problem is rather: what are the norms of the community in which people comment, and how are those enforced? However, we’re not trying to fix comments for the internet.What we’re doing is to design tools to help build better communities, specifically for news organisations. It’s a very important distinction. We aren’t trying to change everything that is happening on the internet. Instead of saying, “How do we make people behave better?,” we turn around to these news organisations and say, “What do you actually want out of your comments?”