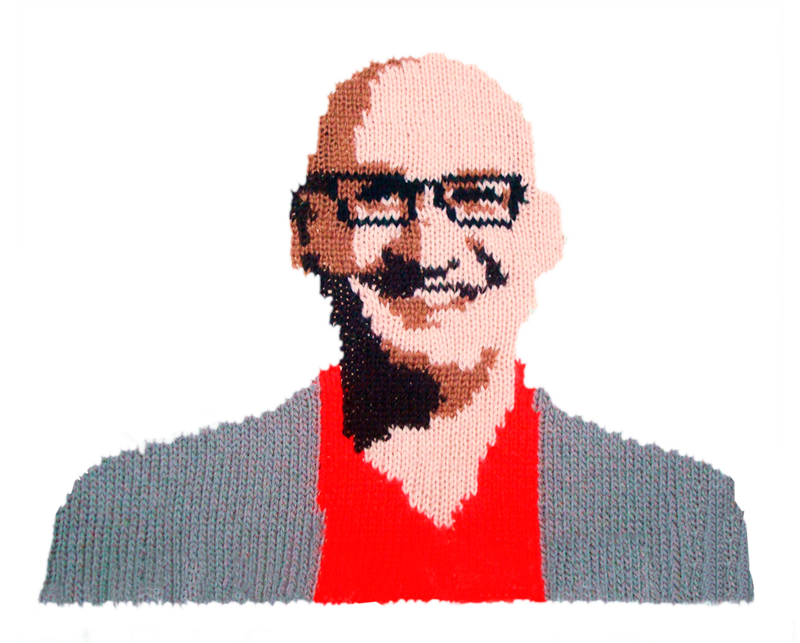

While the big digital players are entering the game (Facebook is securing financial licenses across Europe…), the traditional world of banking is in need of a disruptive evolution. Not only in terms of services and digitisation: innovation in design thinking, branding on transmedia, and strategic communication, are each day more crucial to adapt to this new environment. When Holger Spielberg was in charge of digital private banking at Credit Suisse in Zurich, he was often called the bank’s “head of innovation”. And he himself admits that his role at the Swiss bank was that of a digital evangelist as much as anything else. Spielberg was Paypal’s head of mobile payments and retail services before leading technological development at Aareal Bank, which specialises in property financing. We spoke to him about banks’ identity crises, innovation and disruption.

Holger, in early 2015 you gave an interview for a magazine published by your then employer, Credit Suisse. You said that banks are standing at a crossroads and that the digital revolution of banking is under way. Nearly two years later, what’s the state of that revolution?

I stick to my assessment. And I think the implications of that revolution have sharpened. Technological developments, changing user behaviour, social trends – they obviously have an impact on how we do business, specifically for banking. But what’s actually happening is disruption. Less on the technology side: it’s a disruption of identity and self-understanding. Who am I and who am I going to be in the future as an organisation? Identity is defined by your history, your DNA, your legacy, but also by how you project that legacy into the future. It’s not really clear for most organisations who they want to be in the future. And that disruption in identity is, in my view, the most fundamental disruption that is happening.

In terms of revolution, banks are struggling with the onslaught of new developments on the technical side. Not a single fintech has yet threatened a bank. But the complexity and the aggregation of the new players is becoming very dangerous. There are now big companies in the world – I call them the four horsemen, Amazon, Google, Facebook and the likes – for whom stepping into banking and financial services is easy because they already have the user relationship. They know their users better than those users’ families do. That’s a big threat.

Coming back to the identity crisis, if you don’t know which role you’re going to play in the future, it’s really hard to make decisions about digitisation. What do you invest in? How do you transform your IT infrastructure? Because somebody is going to ask you about the business case for investing in a new platform. And for the business case, you’ll have to make some assumptions about what the future is going to be like, and if that future is unclear, that brings us back to the situation banks currently find themselves in. They have difficulty making decisions in the here and now because the future is so uncertain.

What I’m saying is: the revolution in banking is really an internal struggle rather than an external one. And the homework to be done is most significantly on self-understanding, on the role of the bank in the future. Once that’s clear, everything becomes easier: digitisation, where to invest, with whom to partner and what services to offer.

That internal disruption and uncertainty about identity – does that stem from an uncertainty about what customers want, what problems they want to have solved by their banks?

Not really. Consumers change their behaviour independently of what we think. But again, if consumer behaviour is changing and that change is being driven by Facebook or Google, by players who have nothing to do with banking, that makes it very difficult for a classic bank to offer these services as well. And that’s the minimum requirement. You just have to adapt. But the internal procedures are not prone to necessarily address the needs of the customer.

Even if you have an online or mobile interface, these interfaces to a large extent still connect to old-fashioned legacy systems.Changing the interface is easy compared to the challenge of internal transformation. That’s why the first wave of fintechs were focused on frontends. They sucked. Banks hadn’t understood it. So now banks have started on a more collaborative note. They’re working with fintechs, or learning from fintechs, and addressing a modern website and a modern interaction flow as a minimum requirement.

Yet the challenge still remains on the backend side. With a changed interface you’re addressing your current client base and maybe attract a few additional customers, but that’s it. However your money is being spent on internal processes. That’s where the business case kicks in. And that becomes really worrisome because compared to the user interface change, internal transformation is difficult to do.

So companies like Apple, Facebook and Amazon are setting a certain standard and people get used to doing things over their phone. But that’s only a surface. It doesn’t really revolutionise anything. It doesn’t touch on what banks are actually for. What do people want from their banks? Is that being addressed?

I think part of it is being addressed. Because even if there are new players like N26 or Fidor – companies I admire and appreciate – the reality is that there aren’t large crowds of customers leaving their existing banks. Looking at the numbers, most customers appear to have their needs addressed by their bank today.

Do you think most customers are happy with their banks?

Is banking really an emotional process – or is it a necessity of life? Of course you have to differentiate between retail banking and private banking, where people have millions of dollars to distribute and banks have an advisory role for life and estate planning. Yet both are necessary functions. And the emotions in banking only kick in if things go wrong, if money is lost, if your card is stolen. Most banks have addressed that. They have different channels for interactions, which is new.

It happened to me just two weeks ago: I had two transactions in my bank account which I didn’t recognise. I could mark them online and got a phone call from a staff member, and they worked on it and kept me updated. I actually liked that experience. I feel confident they’ll figure out what happened and find a solution. But do I have a happiness factor in banking? Not at all. It’s just a necessity.

What I see more and more is a split of necessary transactions. Daily banking services like payments are moving into into the background. For instance, you can pay your Uber or MyTaxi with Paypal. (I had a little bit to do with this, actually.) So I don’t have to worry about having cash when I’m in London. I just have to confirm that I’ve arrived, and maybe rate the driver. The payment function becomes just context. On the other end of the spectrum, the life-planning and advisory roles of banks are increasingly moving into focus.

Now, are banks doing a great job in all of this? No, not yet, in my view. But the banks that got the point are working on providing real value to the customer instead of pushing financial products – and on making that value tangible. Increasingly there’s a personal relationship, and that relationship can also, if the customer chooses, be a purely technical one. Just this week I came back from Bankathon, a fintech hackathon in Hamburg, and one of the focuses at that event was voice interaction. Connecting, for instance, the Amazon Alexa with banking services. I think a third of the teams were dealing just with that issue.

This brings me back to my earlier point: it needs to be clear who you want to be. Do you want to be a technical background as a bank? Then somebody else will define the front-ends. And that could be fine if your processes are attached to different front-ends. Or do you want to be a strong brand and visible to the customer? Then you have to obviously focus on the customer interaction and the user interface while fixing the backend or connecting with others who can more economically do the technology.

If we look at fintech startups, besides Paypal, there aren’t really any big players. There hasn’t been a fintech revolution. Why is that?

Well, there’s always luck involved. I’ll tell you a story about Paypal. Paypal was founded in 1998 to transact money using the infrared interface of the palm pilot – remember palm pilots? – so that you and I could share money. That was the original idea. They figured out very quickly that this wasn’t going to take off. But what was happening by coincidence at the time is e-commerce – and the Paypal founders were smart enough to bet on that. That really helped Paypal to grow. Yes, part of it was the easy interface and the one-click button. But ultimately it was creating trust in the e-commerce world. So they combined three things. They had the user interface, which was new and easy to use. They were riding a wave which was outside of their control, because e-commerce was happening without Paypal. And finally, they made sure they gained the trust of their customers along the way. And that’s why they’ve been successful.

What is missing now, while we’re all working on user interfaces and user experiences, is this wave that everybody could ride to create growth. What we currently have is fintechs addressing very critical issues in terms of user value. They are addressing them in the stagnant world of banking, but the banks exist. There’s no wave – at least not in the developed world. It’s a little different in Asia, specifically China, where you have huge mobile growth and no legacy banking world. The other area I see are emerging countries, in Africa for instance, where there’s no banking infrastructure at all and stuff is happening through mobile phones. None of these regions have to replace existing infrastructure.

And that brings me back to my problem – which I’m a bit hung up on, I know – namely this feeling that there really doesn’t appear to be a problem to be solved. The only need I see is for more transparency. What do you think?

I wouldn’t say it’s the only need, but I would strongly agree that transparency is one of the main topics to be addressed. If you open a bank account, the process often takes weeks, you don’t know where you stand, and suddenly there’s another request for a document you have to bring in. It’s a process that creates mistrust or at least confusion.

The other side of transparency is, what actually happens with my money? What products or investment opportunities do you have that I understand as a customer? Banks’ business model used to be that they knew about investing and the customer did not, and that’s what they’ve been selling. Now you can get robo advice, you can find information on the internet, you can have peer groups to discuss your investments. You get on an equal footing and suddenly you have much more transparency because the discussion between the customer and the bank becomes a very different one.

You worked in consumer-focused finance for a long time, both at Paypal and Credit Suisse, before moving into property finance. However, you stayed at Credit Suisse for only two years. Why? Did you feel your work there was done?

I think what we did at Credit Suisse was very relevant and very forward-thinking. But is our work done? Not at all. It simply takes a long time. And Credit Suisse has to focus on bigger issues than digitisation. It’s a Swiss bank under non-Swiss management with a global scope in private banking, investment banking and corporate banking, and in Switzerland even retail banking. You can come in with a digital mindset and say, well, we have to change our customer experience and some inner workings of the bank, but the real question is: where do we start? Who do we want to be in in the future?

The need to address that self-understanding and the strategic direction of the bank was overriding, and I believe it is actually more important than the work we’ve been doing. While I was there a new CEO came in, and he didn’t focus on digitisation. He focussed on the true issues and is now reshaping the bank, even dividing it up because that was necessary. And in parallel the people remaining there are diligently working on very crucial innovation and digital topics. But certainly the work isn’t done and will never really be done.The new normal is that all agility and change is going to be an ongoing process.

Do you expect any disruption in the property finance sector?

No. At Aareal we’re focusing very closely on the value for the customer. We have a very small group of customers who handle large investment opportunities worldwide and we are specialists in tailoring finance deals for exactly these customers. On the other hand, with Aareon World, we are addressing real estate management, facility management. We are selling and licensing software. And then thirdly, and this is important, all our focus so far is B2B. We understand that our opportunity lies in bridging into B2B2C or B2C – an area we don’t address at all today.

We want to do our technical homework, not just to redo our platform internally but to really build our future architecture. Not just the technical architecture, but the logical architecture of who do we want to be in the future. And we want to branch into the consumer space, very carefully, based on our existing infrastructure, our existing clients and our existing business model. We can incrementally move forward. I don’t think there’s going to be disruption because the opportunities are so significant.